WILDER SIDE OF OAKLAND COUNTY

Oakland County is a landscape created by the incredible power of glaciers. Glacial erratics are perhaps the most intriguing of all our glacial landforms, but the name “erratic” often causes confusion for those unaware of our natural history and the science behind glacial geology. It should not be, for in reality, there is nothing mysterious about those two words: glacial erratic, when they are used in combination. Glacial erratics are rocks and boulders of any size that were scraped up from the earth, or fractured from bedrock by a glacier, and then carried by the glacier, and finally deposited in an erratic fashion as the glaciers melted and retreated. That event last occurred during the end of the Pleistocene Epoch about 13,000 years ago, a time we refer to as the Ice Age. It was the time glaciers covered much of our planet and created the landforms and lakes of present-day Oakland County.

Trailside glacial erratics in our woodlands become most visible every November after all the leaves of autumn fall. These seemingly out of place rocks of every size and shape are sometimes referred to and sold as “landscape boulders.” I look at them as the unmistakable signature of a glacier, a statement that clearly states, “I was here,” with the “I” being a land-crushing, bedrock-scraping, boulder-moving sheet of ice almost one mile high.

The process of glaciers advancing and retreating has been repeated for millions of years and will repeat again someday. That takes me to a humorous, but science-based story I first heard when living in Plainfield, Vermont. At that time, I was attending Goddard College and studying glaciers in a geology class. Every winter, the deeply frozen earth of Vermont’s farmable landscape would push basketball size erratics to the surface, making spring plowing difficult for farmers. It’s a process that also occurs every winter in northern sections of the United States, including Oakland County.

That memorable tale of advancing and retreating glaciers and rocks in farm fields went something like this:

A Bostonian from the big city was on his first visit to rural Vermont and noticed a farmer and his son heaving rocks onto the back of their tractor’s wagon on an early spring day. The curious Bostonian watched quietly for a few minutes and finally inquired, “What are you both doing?” “Heaving rocks,” was the farmer’s abrupt answer. Still puzzled, the Bostonian asked, “Where did all those rocks come from?” “The glacier brought them,” was the short response. Not very savvy in the ways of glacial ecology but having a sense of humor, the slightly confused gentleman from Boston looked about and finally said, “I don’t see a glacier.” The farmer smiled, paused, and replied, “Be patient and wait here, it will be back with another load.”

I’ve been having an on-going love affair with glacial erratics ever since I was a talking toddler back in Connecticut. Glacial erratic were probably the first science-based words I learned to use in a sentence properly when I was about five years old, thanks to my science professor Dad. He encouraged my meanderings near our rural house and always answered my “What’s this?” endless questioning, with a bit of extra information. I discovered that the “big boulder” near the edge of the woods was a glacial erratic, and that piece of ice age history became a hangout for me and my two sisters.

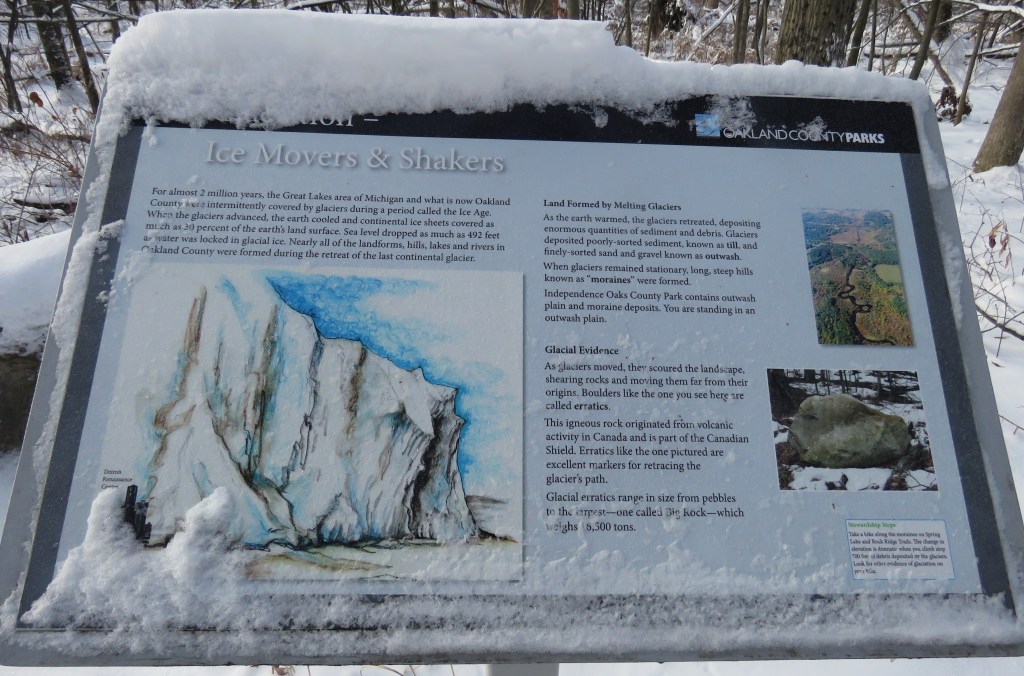

Glacial erratics can be as small as a pebble or larger than a house. Most glacial erratics in Oakland County are not enormous, but still may weigh several tons. Larger ones are likely buried under our forested hills, another landform creation of the last ice age. One of my favorite interpretive signs in Oakland County about our glacial history is located along the River Loop Trail of Independence Oaks County Park and includes a drawing of Detroit’s Renaissance Center appearing next to a glacier that is ten times taller. Glacial evidence is everywhere, perhaps even in your driveway. The gravel that Oxford, Michigan is well known for is actually rounded pebbles that are found in areas of glacial outwash, another gift of the glaciers.

One of the largest known glacial erratics in the world is found at Jasper National Park in Alberta, Canada. That fractured glacial erratic weighs 18,200 tons and was once part of a mountain formation. During the last ice age, a large rockslide crashed down onto a glacier and then part of it, the gigantic erratic, was carried on the glacier to its present location on the prairie landscape. It’s often called “Big Rock,” although its official name is “The Okotoks Erratic,” and it’s about the size of a three-story apartment building. I contacted Jasper National Park for additional information, and they sent photos of their enormous erratic. I also learned from information they shared that the Indigenous Blackfoot peoples name for “Big Rock” is derived from their word for rock, which is “okatok.” Some of the information that came my way includes a legend on how Big Rock split in the middle.

Most of our larger, visible glacial erratics might weigh several tons and are partially buried on slopes in the hilly woodlands of our State Recreation Areas, where their presence is often noted by hikers and trail runners. Hundreds of thousands of others, ranging in size from a baseball to the height of a human, are scattered about in an erratic fashion in our parks, woodlands, open meadows, and fields.

A drive through rural areas of Oakland County reveals glacial boulders have been used in foundations of barns since the 1850s; some foundations have remained standing in place long after their barn’s collapse. Oakland County has thousands of glacial erratics that have been moved to specific locations in highly-developed areas to protect light pole structures in parking lots from cars and guard against snowplow blades.

Many larger glacial boulders decorate driveway entrances or just serve as an attractive natural feature in a yard. Others are used as commercial or residential retaining walls to restrain soils that might slowly slip downward. One of the most attractive glacial erratic retaining walls I have come across is at the Buhl Estate at Addison Oaks County Park. The park also uses glacial erratics as retaining walls on the primitive road to the campground and on their entrance sign.

Almost every harbor along our Great Lakes has large erratics in place to protect against high waves driven by powerful winds, and some roadside historical plaques are mounted on strategically placed glacial erratics.

A drive north to the shores of Lake Michigan reveals some of the most impressive glacial erratics in the Lower Peninsula, erratics appearing in the clear blue waters beneath towering sand cliffs near and at Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore. There are even glacial erratics weighing well over a ton on top of the western dunes of South Manitou Island, a challenging glacial landform that almost always lures adventurous hikers in for a closer look, and then a touch or a sit-upon photo op.

But perhaps one of the most beautiful types of glacial erratics to be found anywhere in Oakland County, or Michigan for that matter, are pudding stones. If the words glacial erratic are intriguing, pudding stone is equally so. Pudding stones are considered glacial erratics because they were transported here by the glaciers. They were formed millions, perhaps billions, of years ago from sand that metamorphosed to quartzite under enormous heat and pressure. They include embedded dark colored pebbles of jasper, as well as red pebbles of quartz and small pebbles with various other colors. According to the Greater West Bloomfield Historical Society:

“During the Ice Age, they were pushed down through Eastern Michigan from Ontario Canada by the glaciers. . . . Some may even contain fossils. . . . Another name for pudding stone is quartz conglomerate . . .”

Physical evidence of our glacially sculpted landscape surrounds us in our daily life, but often goes unnoticed. Go for a hike in the woods of November, drive a rural road, or just explore a suburban parking lot if that’s more to your liking. I bet it won’t take long for you to look about and say to yourself, “Those are glacial erratics, a gift of the glaciers.”

Jonathan Schechter is the nature education writer for Oakland County Government and blogs weekly about nature’s way on the Wilder Side of Oakland County.

Follow along with Oakland County on Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, Pinterest, Twitter, and YouTube using #OaklandCounty, or visit our website for news and events year-round.

Always educational – thank you!

Thanks Mark, Glaciers were certainly a fun– and educational topic!

Drummond Island is a glacial erratic paradise then! One of my favorite places to visit and plenty of pudding stones to enjoy there! Very interesting blog entry – thank you!

Thanks Jacy. It’s been years since I’ve been on Drummond. And I bet it is rich with pudding stones.